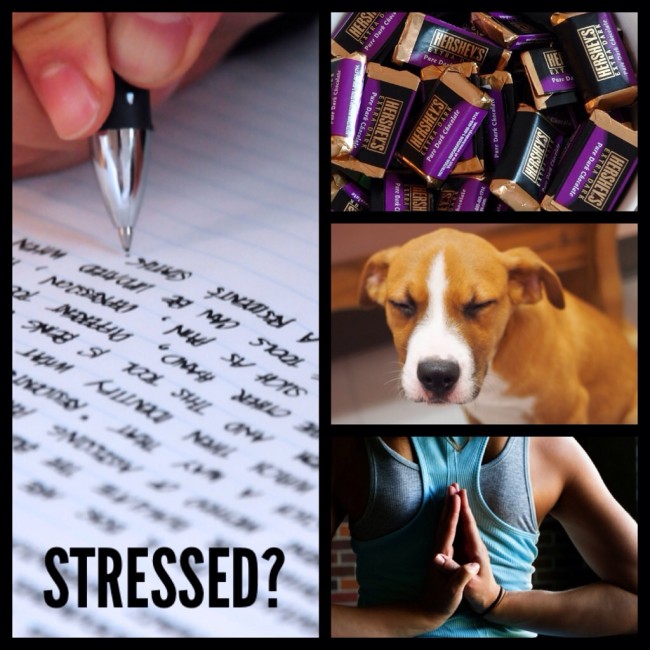

Stressed? Here’s What You Can Do

College students face many stressors, usually related to jobs, family, finances, Greek life, residential life, keeping up appearances, worries about the future (grad school, finding a partner, starting a career), academics, and relationships, including friendships. It’s a long list, with an equally long list of accompanying feelings/emotions, thoughts, and physical reactions, which contribute to behaviors in response to stress.

In order to measure the effects of stress on cognitive functioning, as well as the impact of stress-management techniques, researchers at Peabody College are conducting a study on undergraduates.

Since February, I’ve been one such participant in this six-week study. I attend a weekly group with eight other students, and we receive strategies for dealing with various stressors. The study began with a couple of hours of intensive cognitive tests and ended with a few more follow-up tests.

The first week involved 1) recording daily events and our responses (behaviors, emotions, thoughts, physical reactions) to the events, and 2) delineating the controllable and uncontrollable aspects of stressful situations, in accordance with the saying, “Grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

I found it to be a really helpful exercise. Here a sample review of a day’s events (with a few revisions for privacy’s sake) which I rated a 3.5 out of 5:

“Woke up at 6:15 full of energy, did laundry. Met a professor in the dining hall; he complimented my ‘bright-eyed’ manner and appreciated that I ‘keep the same hours’ as him. Took a four-hour nap in the afternoon. Called my dad. Ate dinner with a friend who gave me great advice and companionship. Caught up on homework.”

Here are my responses to the day:

“Feeling positive about my energetic morning. Felt approval from my professor, whom I respect. Even though I knew the afternoon crash was coming, I feel slightly bad about sleeping for so long because ‘it’s a waste of time.’ Feeling connected to my dad and happy with our relationship. Satisfied to get to a deeper conversational level with my friend. Content with the routine of homework.”

It forces me to reflect on each day and tune into the feelings underlying my thoughts and actions. The stressors I face are often multi-faceted, so it’s helpful to identify the constituent parts.

The second week was all about mindfulness, as described by Jon Kabat-Zinn: Mindfulness means “paying attention on purpose, in the present moment, and nonjudgmentally, to the unfolding of experience moment to moment.” Mindfulness helps us deal with uncontrollable stressors.

We practiced four variations of mindfulness, as follows:

(1) Counting breaths with eyes closed for 2 minutes.

(2) Counting breaths while becoming aware of sensory surroundings (what you see, hear, smell, feel) for 2 minutes.

(3) Use a phrase to counteract thoughts of the past or future (“I am here. Be here now.”) for 2 minutes.

(4) Shift your focus from your breaths to your thoughts and emotions. Don’t judge or attend to the content of the thoughts; just be aware for 4 minutes.

On the third week we learned positive but realistic thinking. Our thoughts can influence how we respond to stress, so it can be helpful to track automatic negative thoughts (click on the link for a worksheet): What happened before the thought or emotion? What was the specific thought? How did you feel? Generate a positive but realistic alternative thought and rate how you feel now.

There are several “negative thinking traps” that are important to be aware of:

• Overgeneralization: thinking that if it’s true in one situation, it must be true in all similar situations

• Focusing on the negative: paying attention to only the times you make a mistake, forgetting positive experiences; or focusing on one negative aspect of a situation instead of the big picture

• Blaming yourself: feeling as if you are fully responsible for every failure and negative situation

• Jumping to conclusions: if it happens once, it will probably happen again and/or lead to even worse things –– this is the classic “slippery slope” fallacy

• Self-reference: feeling as if you are the center of everyone’s attention (especially when you make a mistake)

• Catastrophizing: thinking that the worst-case scenario is likely to happen

• Black-and-white: thinking that everything is either one extreme or another

In my psychology classes, we refer to these as fallacies and cognitive biases.

To challenge these and other types of negative thoughts, it helps to:

(1) Examine the evidence for and against the thought.

(2) Consider the consequences of the thought: How will it affect your emotions, behavior, and physical state?

(3) Generate an alternative but realistic thought: Do not deny or distort the problem, but try to find the “silver lining” of a negative situation.

The best example of this happened when I had a speech coming up and I hadn’t started practicing or even researching yet. My first thought: It’s impossible. My new thoughts––which I had to actively contrive!––were that I had still had some time, I tend to work well under pressure, and the results will be decent if not perfect. I told myself that I was living a balanced life and keeping my commitments beyond academia. And in the end, I had a great weekend, didn’t sleep much on Sunday, and on Monday morning, I was able to give a decent speech.

This post covers the first half of the study. Check back soon for more stress-management tips!